MY FATHER MICHAIL LVOVICH WERZHBINSKIY

by Nina Werzhbinskaja-Rabinowich

Nina Werzhbinskaja-Rabinowich

„Father and Daughter: 52“

watercolor, 1999

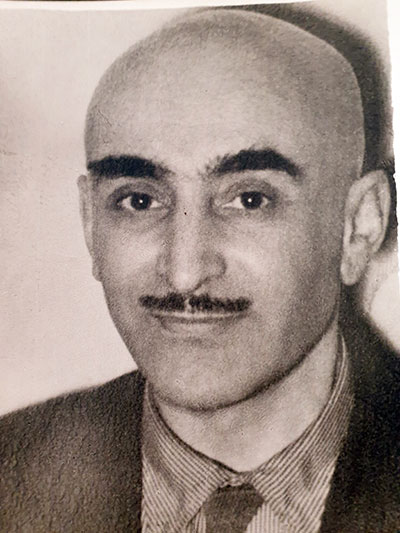

MY FATHER MICHAIL LVOVICH WERZHBINSKIY

This is an attempt to write about my father Michail Lvovich Wershbinskiy. I find it more difficult than to write about my mother: When he died I was not even 15 years old, while for 55 years I had never been separated from my mother, from my birth on until her death. For both my parents it had been a second marriage, both already had sons ten years older than I am. My parents married one year after the end of WWII and I was born in 1947. I mention this right at the beginning to explain how brief this familiy consisting of „Mama-Papa-Daughter “ existed, although I only understand this now, at the time 15 years seemed to me like a whole life. Unlike mama who always answered my questions voluntarily and in detail (and I asked about her family and herself from early age on) I do not remember at all such conversations with my father. Consequently, I was informed about his family and his biography only „second hand“, by mama and relatives. Nevertheless, I attempt to sketch a picture of the man who became important to me and disappeared from my life so early.

Michail Lvovich Werzhbinskiy was born in Peterburg on November 3, 1909. He was the oldest child in his family. Although his father and mother were Jewish Michail was a Peterburgian in the third generation at least. According to Tsarist laws preventing Jews from living inside settlements exceptions existed only for families of first rank merchants and for socalled „cantonists“, namely Jews recruited from small towns serving decades in the Tsarist army. These two exceptions worked as follows: An ancestor was a soldier in Nikolai’s service married to the daughter of a merchant of the First Guild. Whereas this soldier avoided conversion to Christianity , i.e. he kept the religion of his Jewish forefathers. It seems that this was not easy. At my paternal grandmother’s home there hong a small portrait of some young girl, almost a child, painted in oil in Biedermeier style, it is now in the apartment of my cousin in Peterburg. Here, this young woman appeared to me as a merchant’s daughter and future wife of a soldier of Tsar Nikolai. In any case, it was a familiy portrait but I am not sure whether my impression coincides with reality. The family was not, it seems to me, particularly religious. This detail, by the way, I learned from mama and not from my father: my grandfather was after birth given the biblical name „Judas“, for Christians a negative figure. When he started secondary schooling („Gymnasium“) his classmates started to mob him. Then my great grandfather and great grandmother went to see the rabbi and he approved that the name be changed from Judas to Ljev. So my father came to be called Michai Lvovich.

Foto 1: Ljev Werzhbinskiy, my grandfather Foto 2: Mischa Werzhbinskiy as a child

The flat where Mischa grew up was located on Chaikovsky street almost at the corner of Liteyniy Prospect, at that very corner where at the beginning of the thirties of last century the socalled „Big House“ was built seat of the successive secret services, in place of the destrickt court building, demolished in the years of revolution. The Big House was to play a brief role in my father’s life but this shall be told later on. In the apartment reigned a special pre-revolutionary atmosphere which I as a child not yet familiar with the history of my countrynevertheless felt. Although it was at the time, in the fifties of last century, a communal flat like almost all flats in old houses, there were altogether only three families, unlike in those communal flats where I lived, from birth on right to my emigration in 1977, and in our „crow’s nest“1 there were nine, at the best times the „head count“ was up to 30 people. And these three families lived together peacefully which was not the case in our flat.

Old Chippendale furniture, some vases, a piano, a bed with curved columns at the head-end, a chandelier which I adored, a bronze lamp in the shape of a miner, a lantern, carved cupboards and furthermore a carved wooden sofa from the Renaissance simultaneously serving as a chest (it was used by Leninfilm for the film „ The Twelfth Night“ , then restored and had an armrest added to it, it was chopped for firewood during the blocade of Leningrad, a fate which also one of the Chippendale chairs suffered.). I always thought that this dwelling had from the start been my father’s family flat, that after the revolution it had been „made useful“ and other dwellers had moved in, and I learned only very recently that this was not the case. In any event, some rich relatives of his parents had, in 1917, decided to temporarily move abroad and settle there for the turbulent times and to return after everything would have normalized. The family of the young chemistry expert and university graduate Ljev Werschbinskiy with his wife Adelaida and by that time already three children was offered to temporarily reside in the flat and to take care that nothing there would be lost. But the wealthy relatives had not calculated well, quiet times just did not come, it was their fate not to return to Petrograd (Leningrad-Peterburg).

Werzhbinskiys lived there in various configurations for a very long time, up to the beginning of the 21st century, at the start in the whole flat and after it was „made useful“ in two rooms, and later, after part of the family had moved to a cooperative flat on Poklonnaya-Mountain, in one room. And all this impressive furniture remained as it had been entrusted to them for maintaining. I confess that this disenchanted me a bit, from childhood on I found a lot in this family, their quarters, almost aristocratic manners, the furniture which enhanced this, and then this revelation!

Foto 3: Grandma (baba) Adya before the revolution

About grandpa I know almost nothing, he died early, already before WWII, apparently from a heart disease and one spoke hardly about him. Grandma Adya (Adelaida, Llevovich by maiden name), on the other hand, lived a long life by the standards of her times, survived the difficult post-revolutionary years and Stalin’s terror with its horrors, fearing arrest day and night, the evacuation and return to Leningrad after the lift of the blocade. She never worked outside the house but all her life for the family, raised, in addition to her three children, also two grandchildren: the daughter of my aunt and my half-brother, the son of my father from his first marriage. The husband of her younger daughter went to the front one year after the wedding and fell in the battle around the blocade in 1944. Nina, the youngest sister of my father, thus lived as a widow in the family of her mother and older sister. Grandma Adya managed, on a high level, the household. Because all others, i.e. both daughters and the son in law, all of them of course worked, the times were Soviet and women, as is self-understood, equal to men, received an education and worked as specialists. Aunt Nina (Nina Lvovna) was an architect, aunt Alya (Alexandra Lvovna) was, like her husband, an engineer and my father a mathematician. And in her youth grandma Adya sang, she was trained as an opera singer, her voice was low and beautiful. I heard from papa that when bathing her children she often sang the aria of Dalila from Camille Saint-Seans’ opera „Samson and Delila“. And I inevitably recall this when I listen to an enchanting melody.

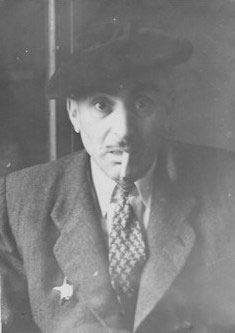

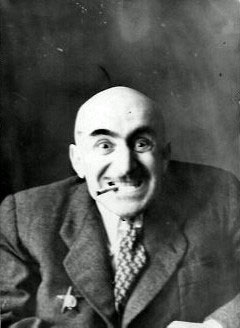

Foto 4: aunt Alya Foto 5: aunt Nina

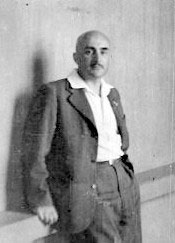

Aunt Alya und aunt Nina were both beautiful and both red-haired with brown eyes. I used to once have a picture, a reproduction of Renoir’s „Girls in Black“, who simply look like both my aunts. Papa, on the other hand, was brunette with a look that one of my female friends called that of a „Babylonean Jew“: large expressive eyes, thick eyebrows and a big, even a very big nose. God loved us, the women in the family, and neither his sisters nor his daughter had such a nose. During and after the war he radically solved the problem of baldness which befell him early and regularly shaved his head, substituting the absence of hair on his head with very thick eyebrows and a trimmed moustache. It is so that I remember him and I do not recognize him in photographs taken before the war: a portly young man with curly hair. This fact favourably influenced my biography: when she received a photograph of my father from the front my mother (they had met shortly before the war and closer relations had therefore not developed at all) was pleasantly surprised by the changes in his looks and the general masculine posture of my future father. This I know from her personally.

Let us turn to the first years after the end of the civil war. Papa and Alya were studying at an institute, the Tenishovskiy Academy near Mochovaya Street (then already renamed Labour School Nr. 15), an outstanding academic institution from which Wladimir Nabokov graduated and even earlier also Osip Mandelstam. Regardless of renamings the teachers there remained the same. Aunt Nina already did not attend this school, she studied at somewhere else. According to papa he successfully participated in class discussing Goncharov’s novel „Oblomov“ without having read it, in leading the discussion and presenting his exceptionally original views. Interesting, how this feature apparently came upon me via genetic inheritance as I, in the 9th or 10th class, had to read this book and did not do so at the time. I wrote some mediocre paper of common places, received a passing degree and after some 30 years I nevertheless did, to my great enjoyment, read this remarkable book and found it of great value. I think that the atmosphere of a sleepy body and soul so masterfully created at the start of the book had led also me into sleep.

It was rather mama than papa from whom I know that at the period of the NEP my father’s family had some private property: a hauler by the name of „Trudovik“2 and a shop selling table-ware, it seems. And there my father showed true political instinct and a correct assessment of the situation: he categorically opposed the family holding on to private property and when the NEP ended after a short time the Werschbinskiys-Lleyvovithes had already parted with their shop and the hauler. I believe that saved the family from possible persecutions during the next 20 years.

At the beginning of the 30ies of last century Michail, nevertheless, happened to „inhabit“ a house in the neighbourhood, the socalled Big House, and to spend there a month imprisoned on remand. As a student he had given math lessons to the children of a family where all were imprisonned and the authorities investigated everyone who had often visited that house. But with papa the matter was just equations and they let him go, fortunately.

My father, like also my grandfather, studied at the university, in the department of astronomy for the first year, after which he switched to the faculty of mathematics. And he chose for himself the most abstract field which has no apparent use, namely : the theory of prime numbers. In my imagination this is somewhat most remote from natural sciences and closest to philosophy. His relationship to science was devout comparable to the love of music. He worked also at home at his huge desk always accompanied with classical music from long playing records, in the first place J.S. Bach, closely followed by Beethoven and Shostakovich. Even now I have this picture in front of my eyes: in my parent’s room, half-dark, shines a lamp on the table (of day light, papa loved technical innovations) and I see papa in profile bending over a manuscript and Bach is to be heard.

To the group of friends in this period belonged the future academic3 and rector of the Leningrad university (LGU)4, Alexandr Danilovich Alexandrov, and Andrey Nikolajevich Murin, who later became head of the chemistry faculty, but then all three were students and post-docs. The most important role in my biography was played by the latter, Andrey Murin. He was two years older than my mother Eleonora Gomberg, studied with her in one class in school, they became friends and it was Andrey who acquainted my parents with each other before the war. According to my mother they, together with their three-years-old sons (who were even born in the same month), papa’s son Gleb and mama’s son Alexey, went for a walk in the Admiral’s Garden and at the time nobody foresaw how things would develop in 6-7 years. Michail Lvovich had already gotten divorced from the mother of his son Gleb, the marriage had been very short and his wife Rosa shortly after the birth had left the flat on Chaikovsky street leaving the baby to the care of in-laws. She took Gleb to her after some time but in the course of his childhood and after the war he used to very often be also at grandma’s Adya and the aunts’ Alya and Nina place, and uncle Wasya, the husband of aunt Alya, went to the house on Chaikovsky street every day after school. There, also the younger daughter of aunt Alya and uncle Wasya grew up, it was grandmother’s task to take care of two small grandchildren as the parents were at work all day.

Foto 6: Gleb in the arms of aunt Nina on Chaikovsky street

A year after this memorable encounter of my parents and my older brothers the war broke out. My father was at this time already defending his dissertation and therefore had leave from the army, but he already in the first days following the declaration of war went to the front as a volunteer. At this period the front was approaching Leningrad with enormous speed. Before they left for the front all three men of the family in Chaikovsky street, Michail Werzhbinskiy, Wasiliy Skragan, the husband of aunt Alya, and Iosif Karnibad, the husband of aunt Nina (he also went as a volunteer and did not return from the war), put all their civilian clothing into a large chest. Not this Italian Renaissance sofa-chest but an ordinary one, and what appeared in this chest after the family returned from evacuation? The dress of a sailor and same such socks and there was no sign whatsoever of the civilian clothes of the three men! In the flat changing temporary dwellers were housed and, lacking wood, they had smashed the Chippendale furniture. But a table from this collection having survived damaged due to hibernation next to bombarded glass-less windows nevertheless still exists just as it did a hundred years ago, and at it my cousin Tania, already on Furstadskaya rather than on Chaikovsky street, receives her guests. And I like it all the more as it is not as if it were new: like the wrinkled but still loveable face of a relative. The Venetian chandelier in the shape of a lotus flower had also suffered during the years of the siege: one of its pedals was crushed and had somehow been fixed during the post-war years. The chandelier was not separable from the table on Furstadskaya street. All women and children of the family had fortunately succeeded in being evacuated to where they had to live for more than three years in difficult conditions, however incomparable with the terrible lives (or deaths) in besieged Leningrad. Both my aunts, Baba Adia and little Tania, ended up in the town of Akmolinsk in Kazahstan and the four years’ old Gleb was sent on evacuation with the kindergarden and without his mother Rosa who had to remain to work at the factory where she was employed as an engineer. But the train with the children in which Gleb travelled was targetted by enemy fire from airplanes, the progress of the fascists being so fast, travelling by the train could turn out fatal. He remembers how all children were led from the standing train and ordered to lie down on the rails beneath the wagons. My father who just attended a short preparatory course, from mathematics to artillery, became commander of a flak battery on the Pulkovsky Hights near Leningrad, they shot at German planes approaching to bomb the city. From my brother on my mother’s side, Alexey, I recently learned that Michail Lvovich got this post not only due to his mathematical capabilities but his unusual artistic talent: he was gifted for music , he had a wonderful ear for music, he could whistle long melodies from classical works of music. This had been noticed by some professional in the miltary who was also a musical fan. He separated my father from the other recruits, learned that M. L. Werzhbinskiy was a mathematician by profession and papa thus became commander of the battery PVO (air defence). A remarkable document still exists, a letter father wrote in August 1941, thus before the blocade of Leningrad, asking friends to send him a book about „outdoor ballistics“:

„7/VIII 41 Dear Olya!

This letter is entirely factual. I ask of you a big favour: please, send me in a package some book regarding outdoor ballistics. But only something reliable with a detailed mathematical apparatus and possibly also tables. What happened is that I got an idea which I want to put into practice. This book should deal with the question of the course of a projectile in the air in a mathematical sense, a differential equation. This is very important, I thank you in advance. At this occasion, please ask aunt Julya to send me sweets (if possible chocolate bars) and some soap for washing. Writing paper (better unlined) would not be bad (in parentheses: this is not obligatory). .I received letters from Rufa and Tamara. Rufa’s brother – Oskar is wounded, hopefully only lightly, but in his shoulder and he, albeit, is a painter. Once more I ask for the address of little Gleb. All the best. Greetings to Lidia Yakovlevna, Shosefina, Boris and so on.

Mischa“

This and some other pages of war correspondence together with a drawing from nature „the fallen soldier“ are now conserved together with the archive of our family in the library of the University Notre-Dame in Indiana (see note **)

Foto 7: letter from the front

Foto 9: fallen soldier

Foto 8: father on the front

My father was decorated with the Order of the Red Star which was kept in his desk, and I loved to study it. The shining ends of the star were in my favourite ruby red and the soldier with gun in a silvery circle in the centre seemed to me like the man in the moon. Upon leaving the USSR in 1977 we were not allowed to take this decoration with us and I don’t know where it is now. The text explaining the bestowal of this decoration refers to a „heroic national act“ and enumerates three rather banal sounding occurances at the front from July 16-23, 1944.

Order of the Red Star

About the war papa told me a few things, possibly more than about any other matter from his life. From his tales I know that the trenches of the Germans were so close to their’s that he and his soldiers heard the Germans talk at night when it was quiet and no exchange of fire took place.....As an officer he had an ordinance, a Stalinesque copy of the Tsarist army regime. This man cleaned his boots, his uniform cloak and altogether functioned like a personal servant. To me who was thoroughly impregnated with the class propaganda against the times of the „Tsarist nightmare“ (an expression my father liked to use in jest) this was somewhat strange to hear: my papa as some kind of „barin“, pejorative expression used by lower classes for members of the upper class, and that was not so good. When I, much fearful of physical pain, asked him what it might at all be for, papa explained to me taking an example from his war experience: „See, I once fell asleep at a camp-fire with my feet to the fire. The boots started to burn and I kept sleeping as long as my feet did not get hot or hurt. If there had been no pain I would have awakened without feet.“ This convinced me that without pain you cannot cope. The blanket, however, which was sown together from pieces of father’s officer’s uniform cloak after the war has accompanied me all my life. It is now in my Viennese apartment und reminds me of the incident with my father’s burnt boots at the camp- fire.

And one more thing: from his years in the artillery division his hearing had suffered. I noticed this when we were on the Crimea, in Alupka – he did not hear the cicadas and that was so strange! But his weakness of hearing could never prevent his enjoying music which was so important to him.

In this hot spot, the Pulkovsky Hights, my father had spent all the war years with the exception of the last months when his unit moved to Latvia from which he demobilized in the rank of a lieutnant. Tanya, my cousin, remembers when he came to the flat on Chaikovsky street for the first time even before demobilization (the family had already returned from evacuation) with soldiers from a delinquent bataillon. My father had to bring them somewhere but there was no place for them to stay overnight. They slept a few nights in the kitchen and according to Tanya’s memory they

chopped firewood.

I shall now start the part of the story when I enter into my father’s life or rather HE enters into mine, and it is possible to not only recall facts conveyed to me by third persons but also personal impressions from the few years we spent together.

After the war my parents were in a situation which one could not call by any means a happy strong marriage. Mama left Alma-Ata where she had spent three and a half years in evacuation together with her son and mother, united with the father of her child. Semion Michailovich (as friends called him, or rather according to his passport, Hajrula Habebulovich) Machmudov, graduate of the LGU faculty of linguistics, had as a young specialist shortly before the war been ordered to work at the Kasah National University. Next, he became an important linguist and until his retirement was head of the group of Russian linguistics at this university which had been established in 1934 in Alma Ata, and in 2010 the linguistics department was named after him . The plan had been that Machmudov would, after a few years, return to Leningrad to his wife and child and look for work there. As the saying goes, humans plan but God decides: the war started and instead of this return to wife and child the latter fled before the closing of the blocade-ring from Leningrad to Alma-Ata which took them two months full of enormous difficulties but they managed. In early spring 1942, after the first winter of the blocade, my mother Eleonora’s mother, grandma Marija Semionovna (by birth she was called Miriam Bella but the passport contained the „Russian version“), escaped from Leningrad across the frozen Ladoga-lake (the „path of life“) and also reached Alma-Ata. Yet another relative also showed up there, namely the socalled „uncle“ Ivan Michejevich Chekulayev, who in the family was called „Uncle Wania“, and after that never parted from the family again. He arrived as an invalid from the short and bloody Finnish war, a contusion, an injury to his head, I shall return to that later. And so all these five live in a dormitory for students, teachers and their families, at first in one, later in two rooms. The first marriage of my mother was, to be exact, unusual. Semion came from a Tartar village, his mother did not even speak Russian, he was a very talented but difficult man with great problems, partly with alcohol, and my mother had received two types of education: in a conservatory (for piano playing) and a degree from LGU in Russian literature (after the war also in history of art). From the very beginning there were frictions and under the conditions of living side by side as a big family in a dormitory, with the restrictions due to the war and also felt in the hinterland – relations broke down more and more. As soon as the blocade of Leningrad was lifted and it became possible, even though with difficulty, to return to the city, my mother quickly went there, leaving behind in Alma-Ata her son, mother, uncle Wania and husband Hajrula Habebulovich Machmudov, in order to secure for herself a teaching assignment at LGU and reclaim her room where people from bombed-out houses already lived. Her mother, the little son and uncle Wania returned to Leningrad within a few months but Semion Michailovich (or Hajrula Habebulovich) Machmudov did not return. According to Eleonora she never considered her departure from Alma-Ata as the end of her marriage to Machmudov although relations were already far from what they had been in the pre-war years. After some time, friends wrote to her that Machmudov had a woman- friend who awaited a child, from Semion himself Nora never received any information and after the official divorce he for the first years refused to pay alimony. In any event, mama ended up free from marital ties when she was 32 years old.

Michail Lvovich’s personal life after the war developed as follows: he got separated from the mother of my half-brother Gleb in 1938 when the child was less than one year old. I learned relatively late from my mother that after this separation my father had a lover called Lilya who had survived the first months of the blocade like my grandma, broke through the encirclement on the „path of life“ and died from famine on the way to the hinterland. In a short letter from the front addressed to a good relation called Olga Rybakova my father in a few words writes about these tragic news which reached him after months of uncertainty: „22/VI 42 Dear Olya! On the 18th I received a letter from Boris, dated May 27. He informs about the death of Lilya Lurye and her parents. This was already three months past. They only made it to Kirov. For me matters are as before, my mood is not good which, by the way, is entirely natural!“

As I already said my future parents during the war wrote to one another a few times (see the masculine foto of papa, impressing mama) and here they and their families were once again in their native Leningrad. Grass widow and grass widower. As a veritable gentleman my father, however, met with Rosa, his first wife and mother of his son Gleb, and suggested to her to try to start a new life. After the war with its horrors, losses and shattering experiences it seemed possible to mend the broken past. Rosa declined. As I now know there was some Lonya in her life (apart from his name I know nothing about him) Rosa hoped for him to take serious steps and therefore told my father No. So she was and stayed alone to the end of her life. And papa with a light heart turned to my mother Nora and was accepted! And I thus received the right to live, because if I were the daughter of somebody else I would not at all be who I am. In any case, nobody told me how my parents got closer after their acquaintance a year or two before the war and after the return to Leningrad in 1945, but it was undoubtedly some kind of process about which I will never find out. Mama only told me about the father’s foto from the front and the impression it made on her, no details furthermore.

Father changed the room assigned to him by the city and moved to a communal apartment in the district Vasilyevskiy-Island, where my mother had lived with my older brother, little at that time, and to where she had succeeded to return. To this very place, to our „crow’s nest“, also moved my grandma on the maternal side, together with inseparable Wania. We were „priviledged“ – we six had (when I was born) a total of two big rooms while some families lived five to one room. One toilet (years later there were two), one bathroom and a large kitchen to which it took 50 steps to reach from our room. For papa the location was convenient: he taught at the Mining Institute in this district and our house was located at the corner of the Bolschoy Avenue and line5 number 4. Mama went/walked to work to the LGU’s historical faculty on the quai from the sphinx to the left and papa from there to the right, unless they used public transport. The household and most of the childcare was taken care of by my grandma and uncle Wania – the parents worked a lot as teachers and scholars, work in the university and the Mining Institute also required research and publication. Me and my brother had nannies – girls from the villages who had come to the city in order to escape from the kolkhoz where working conditions were unbearable, they had no passports to prevent them from running away to the cities. The way to escape after receiving a passport consisted for boys to serve in the army (three years as a soldier or five as a mariner) and for underage girls to serve in cities. The nannies also lived with us, in a part of our children’s room separated by a cupboard. I recall three of them – Marusiya, not so young, afterwards Luciya, very young, who attended evening school while living with us, and Tonya. She was the last of the nannies, I was about nine years old when she suddenly disappeared without telling anybody anything. And after half a year policemen came to us and inquired about Tonya – she was part of a thieving gang and they had all been arrested. Tonya entered the family folklore with her favourite expression: „ I am an honest girl!“

My parents lived in one of our three rooms. Their socalled „big room“ was an office, a library and a bedroom combined and when guests visited us, also a guest-room. It was a very beautiful room with an open fireplace and a high stove with Dutch tiles and with an alcove with four windows. To heat it during the at that time still hard winters (temperatures fell every year below 20 degrees Celsius and sometimes lower) was practically impossible. I recall that before the introduction of central heating beginning of the sixties my mother played Chopin on the piano wearing woolen gloves. This piano, a Pechstein, bought for my mother by grandmother, had been moved from Elisabetgrad to Petrograd already in 1923 (until 1924 it was Elisavetgrad , until 1934 Zinovievsk6, until 1939 Kirov7, until 2016 Kirovograd, now again Elisavetgrad). Papa also played the piano almost daily but I do not remember that he wore gloves.

I write about this to give an impression of our family life, of my father in the post-war period, the conditions of this life. Yet another circumstance, in addition to the „pleasure “ of living in a shared flat, exceptionally poisoned the atmosphere: after a short euphoria regarding the new son in law my grandmother and uncle Vania (especially the latter) hated my father Michail Lvovich. A typical trait of my grandmother consisted in that everything new pleased her tremendously, whether it was the datcha to which the parents drove us for the whole summer (we rented a room or two near Leningrad and in a different place every summer, if the parents went on vacation they slept in the car) or the new housekeeper. Immediately after that she saw in all new things only the negative. And for uncle Vania Michail Lvovich was a sort of „barin“ – the latter had no inclination whatsoever to house keeping, while uncle Vania slaved as much as his health following injuries permitted. And as uncle Vania succumbed every month to a brief period of boozing– on the day he received his pension he spent it all on alcohol, but did not touch what was entrusted to him for the household – so much his feelings towards papa expressed themselves in scandals comparable to the eruption of a vulcano. And only when nocturnal dreams started to torture me at the age of six or seven in which papa appeared as a fascist collaborator indicating where enemy airplanes should fly to bomb „our“ people, only then was uncle Vania forbidden to spread propaganda against my father in my presence.

Foto 10: my father with me at the Gulf of Finnland, 1954

Regardless of what is written above a lot in the life of my parents went harmoniously. They had common interests, wonderful friends who regularly gathered at our home around the dining table in the „guest-library-office-bedroom“. Among the friends of my parents I would like to mention Solomon Grigorevich Mihlin, a remarkable mathematician, Michail Shlomovich Birman, named „Mishula“, an acquaintance from the circle of mathematicians of the Pioneers’ Palace, which until the war my father had led and was attended by Birman as a student. Birman later became a teacher of Michail Lvovich’s son, my brother Gleb. Frequent guests in our home were Georgiy Michailovich Friedlender, a scholar in literature and collaborator at the Pushkin House, Laura Alexandrovna Viroleinen, a scholar in literature and translator from the Finnish language, her partner Naum Iakovlevich Berkovskiy, an eminent scholar in literature, critic of literature and drama, and many others. Especially close was our relationship with Rebekka Lasarevna Slatogorskiy (also called Bekka, Riva or Slata), a remarkable woman, teacher and scholar of the German language. Having neither a husband nor children she was always surrounded by friends and former students of all generations. All her life the former inhabitants of a children’ home kept in touch whom she as a young teacher had led away from Leningrad before the blocade and with whom she had lived in the hinterland for three years. To her circle of friends belonged her former pupils, and when she later became a teacher at the Herzen(8)-Pedagogical Institute, also these former students. Her last work assignment was teaching (and later consulting) at the Institute for teachers’ training and from there she made new friends among the attendants.

Foto 11: from left to right: Bekki, Misha and Nora, 1960

Foto 11: from left to right: Bekki, Misha and Nora, 1960

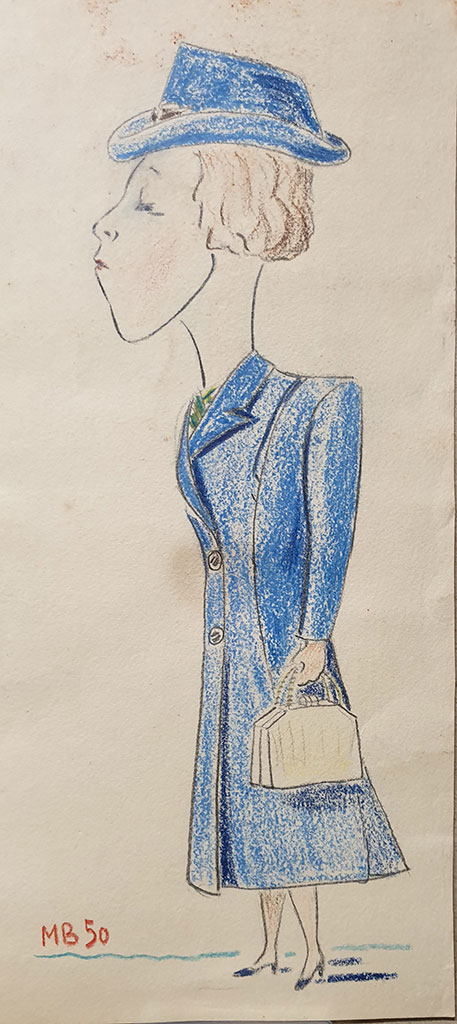

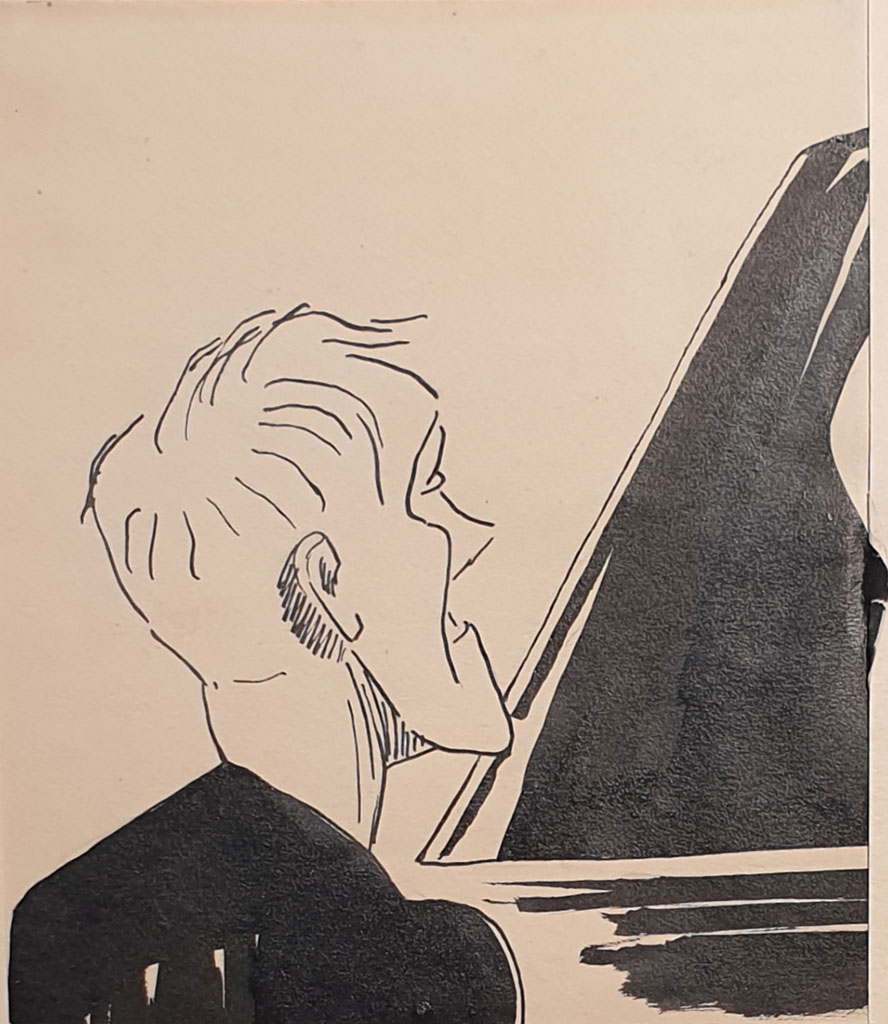

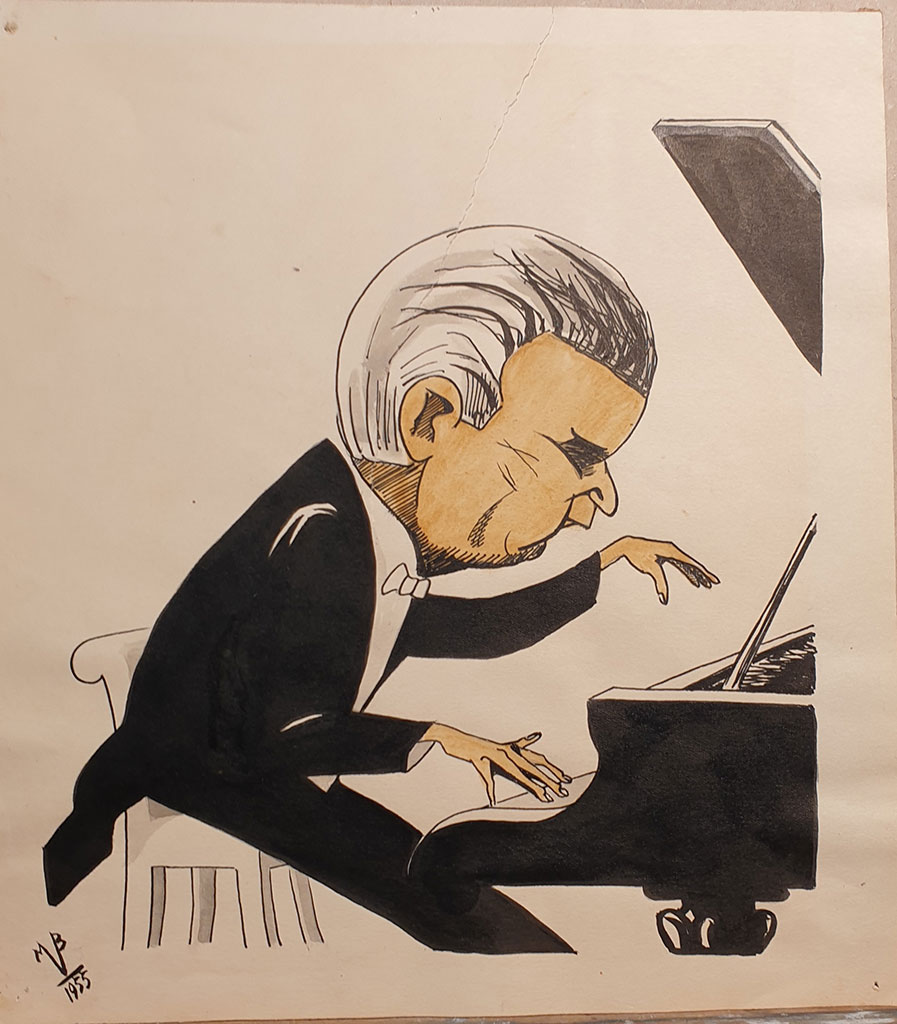

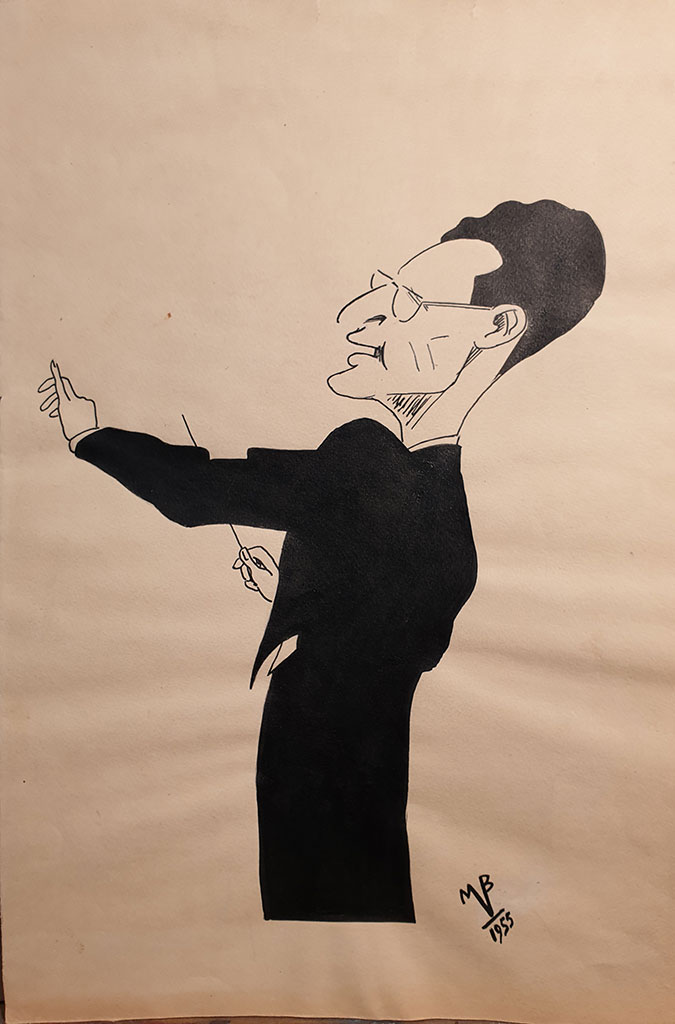

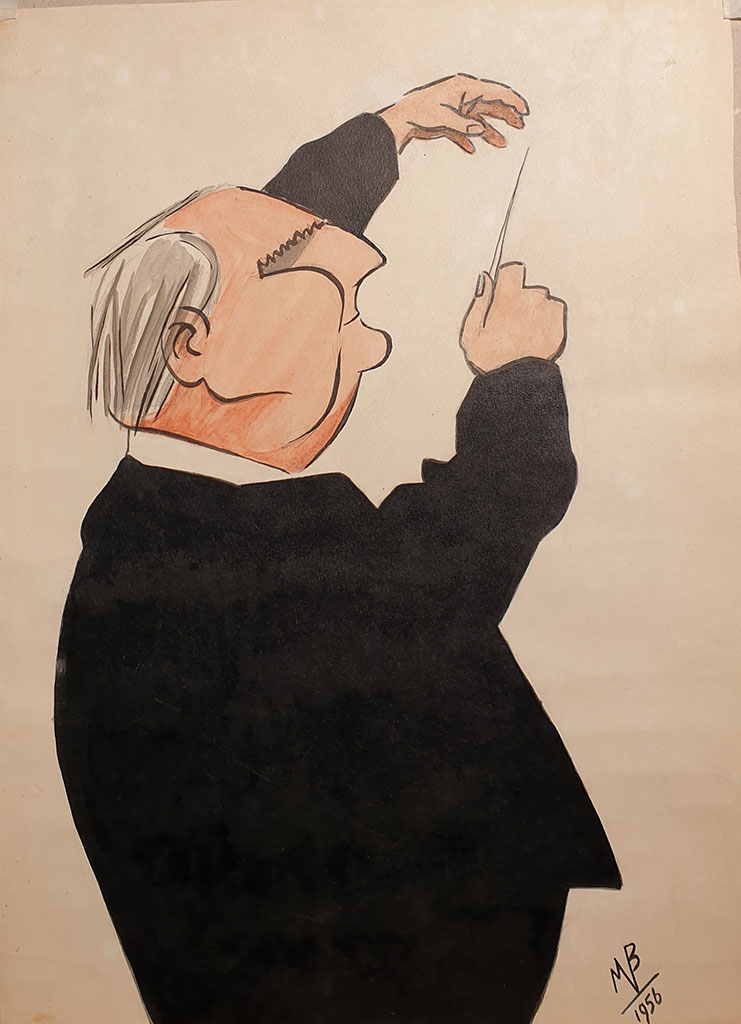

My parents were genuine music lovers, by current standards „fanatics“ of classical music, going to the philharmonic concert hall was for them like attending mass for church goers. They queued for tickets entire nights in order to repeatedly inscribe themselves in lists for concerts they especially wanted to attend and to be able to buy tickets months later. Mama did not understand anything about papa’s specialty, mathematics, in this she showed herself as feeble-minded even by school standards (this, unfortunately, also was inherited by my two daughters, not by me), whereas papa passionately loved fine arts, the field of my mother, and as an amateur himself drew a lot. His specialty were landscapes in water colour and wonderful caricatures, often of musicians and scholars of music known from concerts in the philharmonic concert hall.

Yet another passion of Michail Lvovich came to the fore after the war which he and his brother in law, the husband of aunt Alia and father of Tania Vasilia Alexandrovich Skragan, fully fell for. They both became passionate car drivers. From the beginning of the fifties and until his death father had three cars consecutively. The first one was a „Emka“(9). It had been pulled out of the drainage canal, so I retell the myth which I listened to in my childhood. This car I never saw: Papa was not allowed to take children on board as it was so unreliable. It was replaced by a Moskvich, an old model, and this car I remember well. In it we drove to Baba Adia on Chaikovsky street, to our annually changing summer datchas and on summer excursions. I remember my first journey „abroad“ in the car, to Latvia, somewhere near Riga. On the way, mama read books to papa so he would not fall asleep, he called her his „radio-station“. At this time and in this model there was no radio. After the old Moskvich he changed to a new Moskvich model. Papa adored the car and spent a lot of time with it and in it. I recall an episode when the family took to the forest. All search mushrooms and collect berries but papa stays in the car and says that he would rather read. We returned after a few hours – father’s feet stick out from under the car! He pokes around in it, checks something and repairs.

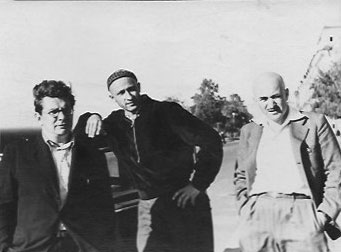

Foto 12: father with an acquaintance by the car „Emka“ Foto 13: father behind the wheel

Foto 14: father by the Moskvich

Without us children my parents undertook short excusions with friends along the Golden Ring(10) , drove to Kiev and so on. Journeys abroad were then unimaginable. For an individual they were altogether unthinkable, not only to the West but also to countries of the Eastern bloc. Travel permissions in tourist groups were rarely granted and one had to go through all sorts of commissions and examinations of trustworthiness, as if one was to go on a spy mission to an enemy country rather than a 10-days trip to Poland or Czechoslovakia. Thus, Michail Lvovich did not once in his life leave the Soviet Union. My mother and I long before emigration had already once been to the GDR upon an invitation by friends. This was my mother’s first journey abroad, at the age of 56. At first we were refused by the authorities(11), mama appealed and in the end we received permission. One year before emigration my husband and I travelled to the GDR to the same friends, he was 39 years old and this was also his first trip abroad.

Now I would like to turn to the „reliability“ of my father in the light of the ideology in the Stalinist and post-Stalinist periods. While at the front Michail Lvovich had joined the party. To Soviet people one did not have to clarify which one, namely the KPSS(12), there were no other parties in the Soviet Union, unlike socalled twin-parties which existed, even if only pro forma, in the countries of peoples’ democracy. Whether it was for officers on the front obligatory to join the ranks of the KPSS or father experienced a surge of patriotism and hatred against the fascist invaders which created such a need I cannot say. As a matter of fact this did not bring any advantage but rather the reverse. Father „earned“ a reprimand along with a remark in his personal record(13) precisely because he had joined the party. ***

I remember well the day Stalin died. After a few days of radio transmissions of the sad music of „Twilight of the Gods“ by Wagner, mixed with short briefings about the state of health of the ailing leader, it was finally declared that Stalin was dead. Our family like many others who held no love or admiration for the „father of the peoples“ at first not only did not rejoice but were all greatly worried about what would follow him. Would it not be even worse, would not Lavrentiy Beria come to power who was feared even more than Stalin. My grandmother sobbed from the morning on, as a cousin of G. Sinoviev, miraculously having at her time escaped exile, she could not be ignorant about the specialties of Soviet history. Uncle Vania remained gloomily silent– having spiritually been communist (although he had himself left the party long before the war) he hated Stalin himself. Mama, to whom I ran from grandmother and uncle Vania to convey the latest news, silently embraced me, took me under her wings like a bird her chicks. In the evening papa, mama and myself went to Chaikovski street to see father’s family. The adults held some conversations which I did not understand, with worried expressions in their faces and I decided to show off by a „poem“ which I had just composed. It consisted of pieces of phrases which I had heard on radio, I remember the first, second and fourth lines:

To beat it stopped, the heart

of our leader

but ta-ta-ta-ta-ta-ta-ta

it shall live forever!

And instead of applause and rewards silence spread in the room where the adults sat, some of them even averted their eyes and I understood with dread that I had done something entirely unsuitable. The only one who found words was my aunt Alia who in an consiliatory tone said how brave I was, but to me my shame was obvious.

Three years later, in 1956, after the XXieth Session of the KPSS papa enlightened me. In 1956 at this session N. S. Khrushev in a secret meeting gave a speech about personal cult, the text of this was „in a secret manner“ distributed to all party organizations but the entire country immediately learnt about it. The following happened: I went for a walk with girl friends after school and suddenly two of them started to whisper to one another and I only gathered that they are talking about Stalin. When I asked what secret they were making they mysteriously answered: „Ask your father!“. As a matter of fact the speech unpublished in the papers spread in closed party assemblies and fathers were more frequently party members than mamas. Now I hurried right away from the little park home and without taking off my coat went into my parents’ room where father was working at the desk and without ado I addressed him: „Papa, tell me about Stalin!“ He laid down his paper and pen, turned to me and very simply and understandably said: „You know, Stalin was like a tsar“. For me, a Soviet school child, the term tsar was linked with the most abject notion of power, arbitrariness and repression. I believe that this was the best explanation given by anyone to me at that age. Since then I asked the old ones a lot, later read about the history of my own country, my interest in history and politics did not wane. After the publication of the article „About personal cult and its consequences“ archives started to be opened a little, unfortunately only for a short time.

And then Michail Lvovich was called to the personnel department of the party at the Mining Institute where he was shown a report about him written by his friend the dean of high mathematics from 1949 to 1955, professor O. W. Sarmanov. I faintly remember this „friend of the family“, he showed up in our house in my early childhood, he was an „intelligent, decent person“. Details of this story I learned from mama much later, after papa’s death. According to her Sarmanov had one weakness: he was homosexual, and for this people were sent to prison in the SSSR. He was not married and had adopted his student, also an unusually „suspicious fact“. I think that this circumstance made it possible to exert pressure upon him and in order to save himself he signed the report on father, a professor at his department and personal friend. In the report it said that Werzhbinskiy Michail Lvovich was an Israeli agent, a member of a Zionist conspiracy and so on. Enough to be sentenced to death or at least to a prison camp for dozens of years. But the „Godfather croaked“(14) in time! Sarmanov apparently got to know that father had been shown the report, the friendship fell apart and in 1955 another scholar became head of the department.

Foto 15: from left to right –Sarmanov, his adopted son and my father

The final years of Michail Lvovich Werzhbinskiy were not very happy ones. In the summer of 1959, at the time of a trip to the Krim, a misfortune occured which by today’s standards was not very serious. Father went with my brother Gleb by car from Leningrad to Simferopol to where my mother and I had to come by train. On the way, in a roadside inn, where they stopped to have lunch papa forgot his jacket. They returned but there was no trace of the jacket. In it there were the driving licence, the car registration paper and the very source of further inconveniences – the party membership card. Mama and I, as planned, travelled to Simferopol but did not proceed to the sea, to Alupka, and the whole family stayed in an inn. For several days my parents went to the authorities, they received a temporary driving licence and other duplicates of documents (the passport had possibly also been stolen, I don’t remember) and my brother and I had a boring time at the inn. Finally, the lost documents were changed into temporary ones and we drove away to Alupka where friends were waiting for us. In the middle of the vacation brother Gleb exchanged places with brother Alexej and then we all, parents, Alexej and I, returned to Leningrad. The stolen documents were never found and the loss of the party membership card turned out to be the worst thing. Father was put in the pillory by the personnel section of the party at the Mining Institute, the loss of this card constituted in the SSSR a very serious violation of law, one could be expelled from the „ranks of the KPSS“ and this could mean a „wolf’s ticket“. A reprimand which was considered the mildest punishment.

Foto 16: Michail Lvovich, 1950ies

With this the strain of misfortunes did not end. Father drew, with dedication and caricatures for the mural news boards, relating ordinary daily occurances at the institute. These caricatures offended someone, he was warned but continued in the same vein. For example, the signature under the picture of a firtree surrounded by oaks read: „the military department celebrates the New Year“(15). As a result Michail Lvovich was regularily dispatched for weeks and even months as a teacher for extra-curricular students from Leningrad to the province, as I recall to the North. He, a candidate of sciences, collaborator of the institute for decades, teacher and scholar whose work was printed in the journal „Publications of the Mining Institute“ and no more young (he was older than 50) at this stage, started to live for long periods in the province in student’s accomodations or inns and feed himself in modest canteens. Father became more and more irritable, he and mother started to fight frequently which had not been the case earlier. I as a teenager (13-14 years old) from my side poured oil into the fire by demonstrating independence from the opinions of the adults in literally every question. At this time Michail Lvovich also experienced misfortunes at work. I took this from mama as my father and I never spoke about it. Michail Lvovich was a talented , in his youth promising scientist. In his discipline he chose the theory of prime numbers, he was occupied, already before the war, with one task. The theory of prime numbers was in the 20ieth century not of central academic interest, few worked in this area, the exchange of results among colleagues was obviously rather limited. Nevertheless, papa remained true to his task, occupied himself mainly exclusively with it and at times there were some successes, his work was published and received favorable reviews from renowned scholars. It was not at all clear whether there would be a result in this effort. And indeed, during the last years of his life it became likely that this task would end in a dead end street. After the death of Michail Lvovich no successor was found for this unfinished work. Some time after his death mama handed over the papers kept in his desk to a former pupil from the circle of the Pioneer’s Palace and later professor of mathematics and mechanics at the university, Michail Shlomovich Birman. He was a specialist in an entirely different area and it appears that nobody followed up on the matter which constituted my father’s life. When I started to write this text I came across a mention of a publication in the internet reading: ABOUT THE DEFECT OF THE SIMPLICITY OF THE PRIME NUMBER /Werzhbinskiy/writings of the Mining Institut, dated 2013-2014.

http://pmi.spmi.ru/index.phd/pmi/article/view/8178

At first I was thrilled: a little less than 60 years after publication of the article in 1958 in the 36th volume of the writings of the Mining Institute my father’s work suddenly became topical again! But disappointment followed: apparently the archive had put on internet all articles published after 1907, among them also some even older works of my father. End of 2019 an entry concerning M. L. Wershbinskyi was added to the website of the St. Peterburgian Mathematical Society:

http://www.mathsoc.spb.ru/pers/verzhbinskii/

Talking in this context about the worsening of the relations between my parents while I wrote this text I had another thought. Mother’s books about art history („Wrubel“, 1959, „Russian art and revolution in 1905“, 1960, „Art and viewer“ 1961, treatise on the book „Ramblers“(16) to be published later) started to be published around the end of the fifties, beginning of the sixties, hence at a time when father’s academic work slowed down. From my memory emerges the following episode: we decided to go to the country side for a weekend, possibly to Pushkin (Tsarskoe Selo). We already sat in the car when the parents suddenly started to quarrel, papa apparently does not want to drive and mama insists. The following sentence is spoken: „Me, what, am I the chauffeur of my wife?“. This I remember because I had not witnessed such scenes between my parents before that.

It is hard for me to write about the last months of my father’s life, they were tragic. At the end of December 1961 New Year approached. My parents decided to celebrate New Year as usual with good friends out of town and I invited my.peers, one girl friend (whom her parents did not let go in the last minute) and three boys to celebrate with me. Grandma and uncle Vania also stayed in town and celebrated in their room. Father was in a bad mood, probably also in a bad state of health, he did not want to leave town and celebrate with company. This was unusual: my parents had always been together for this holiday and as a rule in cheerful company of close friends. Mama did not want to stay in town but papa in his „obstinacy“ (from my point of view) spoiled my first independent holiday without presence of grown-ups. And I remember like it were today: I came to the „big room“ of my parents, the one with the stove and the alcoves, where our evening celebration was being planned and stubbornly started to put pressure on my father: „You both promised that you would go away, you personally promised“. And he sadly said to me: „You won....“. And, really, he left with mama to go out of town. How they spent New Year’s Eve I do not know, only that papa fell ill in early spring 1962. My mother and I were in the „winter datcha“ as usual on a weekend or for the spring vacations, but papa did not feel healthy, stayed in town and called our doctor. She found that his eyes and the colour of his face were yellow and suspected an infectious jaundice. She called an ambulance without delay and they brought him to the socalled Botkin-barracks, the hospital for infectious diseases called after Botkin17Botkin(17). This happened during the last days of March. As soon as she learned about this mama rushed to the hospital, entering it was strictly forbidden but she climbed over a fence and made her way in any case to the doctors. More than a month my father spent in the hospital for infectious diseases as long as it was not certain that he did not suffer from an infectious hepatitis and that his jaundice had a different cause. Some letters survived (with the stamp of the station for infectious diseases) addressed to mama from the hospital, very caring, asking her to seek doctors’ permission to visit him, I have them in Vienna and it hurts to read them. In the Soviet Union the most strict rules of hygiene applied seen from a contemporary point of view, visiting patients suffering from infectious diseases was forbidden with very rare exceptions. Children and under-age people were definitely not allowed to visit any station, infectious or not. Judging from father’s letters they examined him thoroughly, here a quote from a letter to mama: „ I cannot complain about an absence of interest in my organism: in three weeks six doctors and one student examined me, tomorrow will be the seventh“. In his letters he gave mama all sorts of instructions concerning daily life: to punctually pay party fees through the secretary of the faculty, to hand over the documents and keys for the car to an acquaintance, to register in the waiting list for a new car which they intended to buy within a year. He mentioned his saving account. The feeling is now as if I were reading his last will since I know what happened afterwards. In reality, my father did not lose his good spirits he believed in his recovery. He discussed with mama all the results of the examinations, the choice of a hospital to which he had to be transferred in case that he did not suffer from hepatitis. He was not sent home but brought to the Army-Medical Academy where the examinations continued, already not in a department for infectious diseases. Not being an adult according to the rules at the time I was also not allowed into this hospital. They found the cause of the jaundice: stones in the gall-bladder, and proposed an operation which would not be especially difficult. But other analyses indicated that apart from the stones there were serious health problems , namely the suspicion of pancreas cancer, incurable and unoperable. An operation of the gall-bladder was scheduled for mid-May, mama payed (illegally) the professor-surgeon who was to carry out the operation. Mama and my brother Gleb visited my father in the hospital, my other brother Alexey was at this time in Naryan-Mar in the Far North, assigned to work after graduation from the Mining Institute. I saw my father two months after he fell ill and only once, at the beginning of May, they had allowed him to leave for the garden of the Military-Medical Academy. From this meeting I recall just one image: my father, already back in the building, climbs up the stairs to his station. I notice in the windows to the staircase’s landing his figure and face in profile, and he without turning back departs from me.

Some of my father’s letters which he sent from this hospital to me and mama still exist. At this time I was preparing my change to the school of art and general knowledge No. 190, a school preparing for the next level, namely the Institute for Applied Arts named after the sculptor Muchina (today it is called Art-Esthetics-Lyceum No. 190), I intended to submit my documents and works in June. In a letter to mama my father expressed his concern that my, as he thought, mathematical capabilities would not develop in case I entered this school and his doubts concerning the quality of the general education in a school of artistic leaning. Fortunately, he was mistaken: school No. 190 provided an excellent overall education in all disciplines and I never in my life regretted not having followed in the footsteps of papa and my brother Gleb and becoming a mathematician. In his personal letters to me papa calls me baroness Nina and in one of them he, jokingly-teasingly in a scholarly manner, answers my very stupid question why standing on the planet Earth one cannot turn it around(18). In the letters to mama he mentions me almost every time. E.g. like this: „Why does Ninka not write?“. Or: „I embrace you and this one“. In one case he reacted to my written note: “Thank you. But why do you write in such an official manner: Dear Papa. Almost like beloved Papascha.“ Mama he always calls very caringly Norinka. One letter starts as follows: „Norinka, redhead, your eyes are incredibly green. That was the first thing I noticed after you woke me up. And one more thing, Norinka: I am worried, no news from you yesterday. Why? Are all healthy? But, please, only write the truth“.

The operation of the gall-bladder was carried out and the stones were removed. From there the stories diverge: according to one the doctor showed the stones to mama and said: „Fortunately, no more have been found“. According to the other version the cancer of the pancreas was there nevertheless and was not touched. The operation took place on a Thursday or Friday, the following days, May 19 and 20, were a Saturday and a Sunday. There was no professor at the hospital and complications emerged after this planned and by itself uncomplicated operation, the temperature rose, he lost consciousness and after regaining it he suffered greatly. It was probably peritonitis. From the young doctor on duty during the weekend and the rest of the medical staff of the hospital no attention was paid to the patient. Gleb and mama did not leave him and my cousin Tania also took turns at the bed of the dying. Mama told me that at one point regaining consciousness papa looked at her and said: „I saw him“. One can interpret this as one pleases. At this time he already had his first grandchild, the son of Gleb, Alexey Wershbinskiy, whom my papa loved a lot and of whom he was proud. Possibly he had this little boy in mind, possibly not. The three following grandchildren, the daughter of Gleb, Asia, and my daughters Julya and Masha, and his six greatgrandchildren, he did not live to see. ****

Papa died on May 21, a Monday. Mama was so unprepared for this fact that she interpreted his parting from as an ordinary loss of consciousness and asked the doctor: „May be one could apply a cupping glass?“. To this the doctor with irony responded: „Well yes, one could“. With shame about herself and anger about the doctor she later told me about this episode. And brother Gleb who together with mama came home on the evening of the 21st of May said with tears in his voice: „He was so small....“. I noticed later that animals and people appear small in the moment of death. In the note from the hospital the cause of death was given as pancreas cancer, which in any event was not the immediate cause. The fatal deterioration following the removal of the gall-bladder in the post-operation days was the veritable cause but in this manner the doctors rid themselves of all responsibility. How a cancer of the pancreas evolves I learned later. Could the suffering, the lack of supportive therapy and of pain killers (morphium was given only sparingly in the Soviet Union) have been an even more tragic variation and had papa thus been saved months of suffering? Did he have cancer or was the doctor right who, when showing the stones to mama, said: „Fortunately, only this“? I do not know.

Foto 17: grave of Michail Lvovich Wershbinskiy at the

Cemetery in Commemoration of the Victims of January 9(19), in Peterburg, 1990

EPILOGUE

I do not want to end this history on this note and the epilogue will consist of a portrait of my father Michail Lvovich Wershbinskiy the way I see him all these years after his death. May be subjectively but I am not writing an article for Wikipedia. He was a brilliant personality, a person gifted in many domains, emotional and creative. He was capable of love and could show it to his beloved. He had some elegance about him, an excellent taste which was evident in art as well as in his way of dressing. I am not afraid to say: one felt class in him. He also had difficult sides of his character, he could be unusually hot-tempered, explode unexpectedly. This, however, never expressed itself in indecent grumbling or even thrashing (often to be found in Russian milieus, for him though an unthinkable behaviour). Nevertheless, I remember a scene when papa, for some reason I don’t remember, jumps on his glasses on the floor and screams: „To hell, to hell, to the devil!!!“. A typical choleric and an excentric to boot. I was never afraid of him even in such moments.

My parents loved French movies, they started to be shown in the Soviet Union in the fifties after Stalin’s death. The favourite film of my parents was „My uncle“ („Mon oncle“ in the original) of 1958, the director and main actor was Shak Tati (Jacques Tati). Such films were put on either altogether shortly or at festivals. I did not see it at the time but I remember the excitement of my parents. And here in Vienna I could see this film in 2015 in the open-air-cinema in the garden of the Lower Belvedere. I fell in love with the movie, with the personality Monsieur Hulot, the author and performer Tati. He was, in reality, a Russian emigré in France, his last name was in any event Tatitshev. And I had the feeling that a thread ran from papa to me, as if he shared with me his

favourite film.

One of the first portraits I drew from nature in a few sessions with my drawing teacher Yevgeniya Yerofeyevna Bogdanova was one of my father. The pencil drawing shows him sorrowful, even effaced, not the way I remember him. It was made before his very illness beginning of 1962, one might feel a warning. Thus, it always seems in retrospect but at the time nobody in the family had any such premonition. From the long sessions for this work I remember the face of my father so well that I had no difficulty to achieve a similarity of character when I did the double portrait – he at the age of 52 (he did not get older) and myself having reached that same age in 1999.

http://www.ninawr.at/en/47-saal1-en-detail/399-father-and-daughter-52-detail

Foto 18: « Father and daugther:1952»

Nina Werzhbinskaja-Rabinowich,

watercolour on paper, 1999

Foto 19: «Portrait of father», pencil,

Nina Werzhbinskaja, 1961-62

Fotographs and pictures by Michail Lvovich Werzhbinskiy from the 50ies

Self-portrait as a pirate, paper, watercolour, 1955

Portrait of Nora, paper, ink, white, 1950

Nora and Nina, paper, gouache, 1950 Norotchka coming home, paper, coloured pencils, 1950

Pig and linen, fishermen’s settlement, paper, watercolour, 1954

Vasilevskyi Island, crossing of the Big Boulevard and No. Line 4, paper, gouache, 1950ies

Self-portrait, paper, charcoal, 1950ies Self-portrait with hat, paper, ink, 1950ies

Friendly caricatures, for the news wall

at the Mining Institute

1955

Musicians Y. Y. Veinkop (left) and A. N. Dolshansky (right), ink, 1955

Pianist S. Richter, ink, 1955

Pianist prof. Pavel Serebryakov, ink, 1955

Conductor Kurt Sanderling, ink, 1955

Conductor Franz Konvitchny, paper, ink, 1955

Conductor Yevgeny Mravinsky, paper, ink, 1955

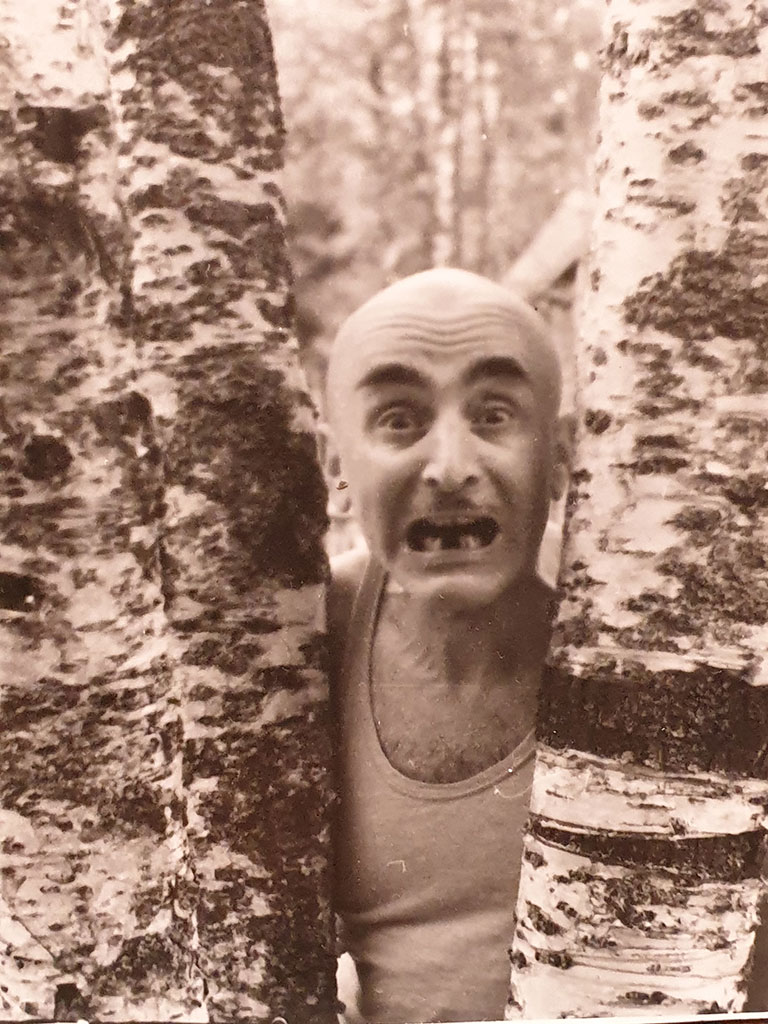

Series of fotographs „ I make roses out of special material“

On the broom

The reverse side of the photograph

Candidate of sciences

A scholar sucks ideas out of his own finger

In a lady’s hat With a cigarette

Speaker Gloomy Misha suuuuch a small one

Uncle Vasia and father, „hunter & dog“, 1955

end notes:

*New Economic Politics, introduced after years of war communism allowing private initiative in entrepreneurship and helping the disrupted country to somewhat get on its feet.

** Gomberg-Verzhbinskaia and Rabinowich Collection, MSE/REE 0013, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Hesburgh Libraries of Notre Dame.

https://archivesspace.library.nd.edu/repositories/3/resources/1944

*** I start in an orderly fashion: at first, Stalin harboured illusions that Israel would become a socialist country – the first settlers from Russia with their Kibbuzim, their Zionist orientation at this time did not consider themselves as ideological enemies of the Soviet Union. When, however, in May 1948, Israel established itself as a state and her orientation towards the USA became obvious all Jews living in the Soviet Union turned for the Stalinist regime into potential traitors and „enemies of the people“. Antisemitism had never abated among the population, after the revolution when a high percentage of the Jewish population actively participated in the „construction of a new world“ it had fallen out of fashion, but during the Cold War it not only broke out anew but became government policy. This was not the first persecution of one particular people in the „brotherly family“ of the multinational state. Following the victory over fascism all Tchechens, Ingushs and Krim-Tartars without exception were declared as collaborators and deported to the steppes of Kazahstan. When Greece, in 1952, joined NATO all Greeks who had lived in Russia for generations were simultaneously turned into enemies of the people. They were sent to „remote locations“ right from their places of work without having time to even return home. For all Soviet citizens had in their passports, after first, father’s and family name as well as citizenship, an entry relating to NATIONALITY: Russian, Greek, Ukrainian, Georgian, Jewish etc... whereby the latter bore no relation whatsoever to religion. By the Nazi principle of „blood and race“ a given individual was determined to be Jewish independent from whether he or she was a „Jud“(20), Orthodox, Muslim, Catholic or Protestant. Such was the position of the „father of the peoples“, Stalin, about whom V. I. Lenin in 1913 in the emigration had written to Gorki who was concerned about the rising nationalism: „Now a remarkable Georgian settled with us and writes for „Enlightment“, a communist periodical, a long article, collecting all Austrian and other materials“. He was referring to the theoretical work of Stalin „Marxism and the national question“ written in Vienna and published in 1913. After the October revoluton Stalin was People’s Commissary for matters of nationalities.

One of the last terrible trials of Stalin’s time became the „ doctors’ affair“. By denunciations in 1949 this affair was prepared step by step as a Zionist „plot of Kremlin doctors“, annihilating the Central Committee and the government. In January 1953 an official announcement appeared about the arrest of the doctors-conspirators. They were all thrown into prison and tortured to obtain confessions (one doctor died from thrashing), all newspapers and the radio trumpeted about the plot . With rare exceptions the „doctors-pests“ were Jews, this fact was constantly emphasized. It did not come to condemnations: on March 5, 1953, fortunately, the „Godfather croaked“, as contemporary opponents expressed it. One of the first signs of the ending of terror were the release and rehabilitation of the Kremlin doctors on April 2, 1953, a month after Stalin’s death.

**** Apart from his first grandson, Gleb’s son Alyosha Werzhbinskyi, born in 1961, whom Michail Lvovich lived to see three further grandchildren were born after his death. In 1969 Gleb’s daughter Asia Werzhbinskaya, in 1970 my older daughter and in 1981, already in Vienna, my younger daughter were born. And there are also great-grandchildren: in San Francisco, into the family of Alyosha Werzhbinskyi Ilya, Dasha and Mark were born. In Vienna elder dauther's daughter is growing up. Asia Werzhbinskaya has been living in England for a long time, in London for the last few years, and she took up British citizenship. Her children, Pablo and Francisko, speak three languages: Russian, English and Spanish, since their father is of Mexican origin.

In Russia, more precisely in St. Peterburg, of all of Michail Lvovich’s relatives only a niece lives, the daughter of my aunt Alia, Tatyana Skragan. I myself emigrated in 1977 with my husband, my mother Eleonora and my then 7-year-old daughter to Vienna and here my younger daughter and my granddaughter were born. My mother Eleonora died in 2002 and is buried in the Vienna Central Cemetery. My brother on father’s side, Gleb, emigrated with his wife, his son Alyosha and his daughter Asia one year after we did, in 1978, to California. Gleb now lives with his wife in Berkeley and Alyosha’s family in San Francisco. My brother on mother’s side, Aleksey Mahmudov, emigrated to the USA in 1984 with his wife and son Vadim, he lives in New York.

Nina Werzhbinskaja-Rabinowich

Translation from Russian by Gabrielle Matzner

Vienna, 2019.

1 By „crows’ nest“ an unpleasant situation is characterized in which all present and living together constantly bicker.

2 „Worker“

3 Member of the Academy of Sciences

4 Leningrad State University

5 Lines in Leningrad are (originally) the (two) sides of a canal.

6 Grigory Zinoviev was a prominent revolutionary murdered 1936 during Stalin’s „Great Purge“ in the thirties of the 20ieth century.

7 Sergei Kirov was a prominent revolutionary, murdered, most likely on Stalin’s order, in 1934, his murder became the pretext for t he „Great Purge“.

8 Aleksandr Herzen, 1812-1870, Russian writer and political thinker

9 A car called „Gas M-1“ was produced between 1936-42 in the Soviet Union, Gorki, possibly the first personal vehicle; Emka seems derived from this typification.

10 „Ring“ of old towns, including churches/monasteries, e.g. Zagorsk, roughly between Moscow and St.Petersburg

11 The competent authority was called OVIR which stands roughly for Office for Visa and Registration, under theauthority of the Ministry of Interior.

12 Communist Party of the Soviet Union

13 Every citizen had such a record, a booklet issued by a personnel department, containing. i.a., career details andspecial remarks.

14 The Russian word stands for gang leader in the under-world of gangsters.

15 „oak“ in Russian also denotes a dumb person.

16 Peredwishniki, a group of realist artists, mostly painters, founded in 1870 in opposition to the restrictions imposedby the Imperial Academy, often presenting aspects of daily life in a critical vein and organizing exhibitions in different towns.

17 Jewgeniy Botkin, 1865-1918, the tsar’s physcian

18 This question must have been inspired by reading Baron Munchhausen.

19 On January 1905, the socalled „Bloody Sunday“, Tsarist troops attacked a large crowd of peaceful demonstrators in Peterburg, which resulted in many hundreds dead and triggered further unrest and finally the revolution of 1917.

20 A „Jud“ in the Russian tradition/laguage is a religious Jew (only)